Part One – Jonas and the Bucket

In a shallow area of a creek in Washington, D.C., sits a five-gallon plastic bucket wedged between rocks. Jonas Furberg, co-owner of Blue Planet Scuba, has been eyeing it on his daily commutes, as he drives from Silver Spring, Maryland, through Rock Creek Park with his wife, Heather Tallent, to their shop in the District.

“How did it get there? Who knows? Maybe it blew off the back of a truck,” says Furberg. “I would like to be optimistic and think that people aren’t just winging things out of their car windows as they go through the park.”

A lot of people might not take note of an object like this, but most people aren’t scuba diving instructors. “In D.C., everybody is like, ‘Save the bay,’ and divers are the ones going, ‘The bay goes out to the ocean, so save the ocean,’” says Furberg. “The amount of plastics that we’re seeing out there right now is astounding.”

“The amount of plastics that we’re seeing out there right now is astounding.”

The bucket that has caught Furberg’s attention, like most plastics that end up in waterways, will break apart into smaller pieces over time. Those pieces will get carried downstream toward the Potomac River, into the Chesapeake Bay, and eventually the Atlantic Ocean. Along this journey, the pieces could continue to disintegrate into microplastics, which are easily ingested by fish, birds, and other wildlife, threatening their survival and contaminating the seafood that humans consume.

Plastics often enter waterways through littering and illegal dumping. Rain sweeps the trash on sidewalks and streets, such as plastic bags and bottles, into gutters, which flow into storm sewer systems and drain into creeks. Larger items, such as construction waste, are often dumped illegally in rivers.

Washington-based Ocean Conservancy estimates that eight million metric tons of plastics are dumped into the world’s oceans every year on top of the 150 million metric tons already circulating in marine environments. This is equivalent to five grocery bags filled with plastic for every foot of coastline in the world, according to Plastic-Pollution.org. The website reports that by 2025 the annual input is estimated to be about twice greater, or 10 bags full of plastic per foot of coastline. Plastic has been found in 59% of sea birds, 100% of sea turtles, and more than 25% of fish sampled from seafood markets around the world, says Ocean Conservancy.

However, when it comes to preventing plastic pollution in the Washington area, the tide is steadily rising, as both the local government and area residents are increasingly taking action.

This is why this plastic bucket will eventually head in a different direction. It rests just a few yards away from an eddy, created by a nearby waterfall, where a bundle of trash and debris amass in this corner like junk in the back of a closet. The smell of stagnant pond algae hangs above. Among sticks and wood, floats plastic bottles, food containers, pet toys, tennis balls, flip flops, and other buoyant garbage that has found its way into the stream of this popular urban park.

District resident Michael Haack comments on the trashy eddy while on a walk with a friend and her frisky golden retriever. “This is unfortunately typical,” he says. “These days it’s a global phenomenon.” Haack moved back to Washington recently after living several years in China and other countries. “There’s plastic in everything. I think D.C. is actually a cleaner city than a lot of others.”

Studies support his observation. According to Ranker.com, a TK ID GROUP, Washington, D.C., was voted the 15th cleanest city in the U.S. in a 2007 poll of over 60,000 Americans. But there is still much to be done.

Part Two – The District Acts on an Issue Brewing Globally

Washington, D.C., has passed laws to restrict three types of common single-use plastic items in the last 10 years. The city is celebrating its 10th year of the Anacostia River Clean Up and Protection Act of 2009, also known as the “Bag Law,” which requires businesses to charge 5 cents for each paper or plastic bag given to customers. The District banned Styrofoam and foam disposable food containers in 2016. Single-use plastic straws and stirrers, which are too small to be recycled, are prohibited in restaurants and other businesses as of January 2019. Washington is the second major U.S. city to implement this policy. Seattle took this action six months prior.

Haack supports implementing such bans and recalls his time living with roommates 10 years ago when the “Bag Law” came into effect. “All of a sudden you’re sort of embarrassed if you have to buy a bag,” remembers Haack. “I think that was successful in creating a taboo.”

Washington-area hospitality businesses are also sipping on the single-use plastic problem. Our Last Straw is a coalition of restaurants, bars, cafes, hotels, and event venues formed in 2018 with an awareness that their industry is the primary purveyor of plastic straws. The group, which was created by Farmers Restaurant Group in Kensington, Maryland, partnered with the city’s Department of Energy and Environment to help educate local restaurants and other businesses before the ban went into effect.

“Whether it’s at a stadium, at a game, in a restaurant, we’re wanting to show the world that it can be a win-win,” says Julie Sharkey, the program director of Our Last Straw. “There’s a business case for it, and there’s a case for the environment.”

“There’s a business case for it, and there’s a case for the environment.”

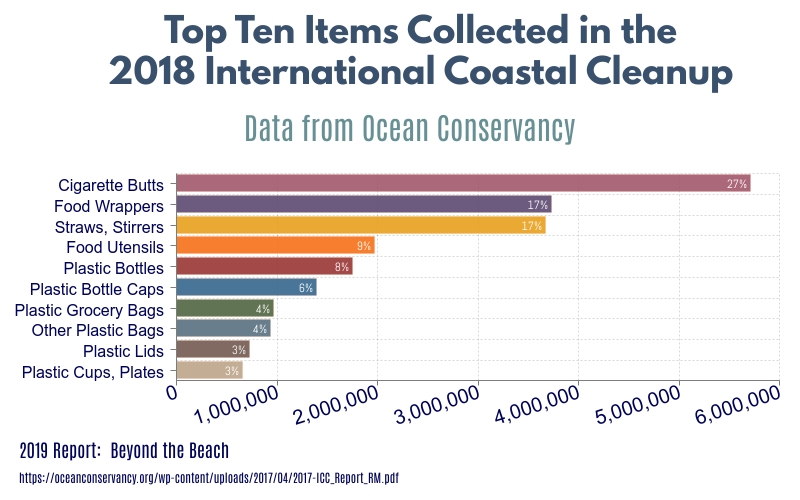

While such bans are small, local actions, they have world-wide implications. More than 220 million pounds of trash has been picked up by Ocean Conservancy’s volunteers in the last 30 years during its annual International Coastal Cleanup. Their reports show that since 2017, all of the top 10 items collected during these events are made from plastic, and this trend is expected to continue. Plastic straws placed third on their list, with over 3.6 million found, in the group’s most recent report of its 2018 cleanup.

Part Three – Washington-Area Residents Wade into the Plastic Problem

Without a nearby beach to clean, Furberg knows the dirty eddy at Pierce Mill well. “The next best thing for us to do is find a waterway that’s near the shop that we could adopt,” he says.

Furberg cites Ocean Conservancy statistics to the 27 volunteers who have gathered under a pavilion in Rock Creek Park on a warm morning last September with a determination to do something about plastic pollution. He is a stream team leader for Rock Creek Conservancy, a non-profit headquartered in downtown Bethesda that promotes the welfare of the park.

Furberg and Tallent have organized cleanups of the Pierce Mill section of the park about four times per year since 2013.

Furberg supports the city’s recent bans on plastic, and he believes the “Bag Law” has been effective at decreasing the number of plastic bags found in the park.

This day, Furberg marshals the volunteers with clear directives: “A group could put in at least a couple solid hours on the eddy by the mill,” he shouts. “And there’s a five-gallon bucket down there that someone could just walk out and get.”

Many of the cleanup volunteers are also customers of Furberg’s scuba shop. However, diving in Rock Creek isn’t permitted, so scooping up floating garbage and wading into the shallow parts of the river is the best that he and his team can do.

Meredith Deeley got her scuba certification through Blue Planet in 2013 and started participating in their cleanup events a year later, including an underwater cleanup trip abroad.

“It’s just such a big problem. How can I possibly do anything as one person?” asks Deeley. “Even if it’s just one animal that I’ve stopped from ingesting plastic or Styrofoam and getting sick, that is a victory.”

“Even if it’s just one animal that I’ve stopped from ingesting plastic or Styrofoam and getting sick, that is a victory.”

The volunteers gear up with gloves and bags that are color-coded to indicate trash or recycling and break into smaller groups. Four people arm themselves with a pool skimmer and head to the eddy.

Each piece of trash must be cleaned before it can be deemed recyclable. The group empties the liquid contents of numerous plastic bottles and wipes junk free from mud and debris before tossing it into white or blue bags.

Natalie McLenaghan, a marine habitat resource specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has participated at other cleanup events and is volunteering at Pierce Mill for the first time today. She can’t help but feel a sense of resentment towards the carelessness that leads to so much trash entering the creek. “This is our local national park,” says McLenaghan. “You would hope that people would want to take pride in it and keep it clean.”

Several members of the National Chapter of Trout Unlimited, a non-profit for fishermen who are concerned about waterway conservation, are also here. One of its members enters the creek chest deep to work along the far side of the eddy. He pushes debris toward the bank using a large floating log and tosses plastic bottles toward the group on the bank. The activity attracts a small audience. A jogger calls out “Thank you,” as he pauses to see what’s going on.

Fishermen, like divers, are also increasingly concerned about the issues plaguing waterways, says Furberg. “The last thing they want is to be catching water bottles.”

Checking in on the team working at the eddy, Furberg takes a moment to join a volunteer cleaning near the five-gallon bucket. “I think it’s full of paint, but I’m not going to open it,” he says as he lugs the bucket to the cleanup event’s trash collection site. “Who knows? There also could be someone’s head in here!”

Volunteers gather near a pile of trash bags as the event comes to a close. Furberg weighs each bag as they are brought back. “That’s all?” asks a child in a disappointed tone after hearing that her bag weighs just under five pounds. “You got the little pieces. That’s the most important stuff to get,” Furberg replies.

Tallent, Furberg’s wife, announces that the final tally is 176 pounds of trash and 35 pounds of recycling. “What’s the weirdest thing you found?” asks Tallent of the team. People call out, “A barbie! A rug! A wig! A bag of garlic! A really nice marijuana pipe set in a box but no marijuana!”

What item was found the most? Dog poop bags, typically non-biodegradable plastic. “With the poop,” calls out a volunteer.

“Can you believe that people actually bother to wrap poop in plastic and then don’t bother to throw it away?” asks Furberg. “If you’re just going to leave it, don’t wrap it in plastic first.”

“If you’re just going to leave it, don’t wrap it in plastic first.”

Furberg doesn’t mention the heavy five-gallon plastic bucket, which now sits prominently among the bags of trash. The item is considered “bulk junk,” because it’s too large to fit into a bag.

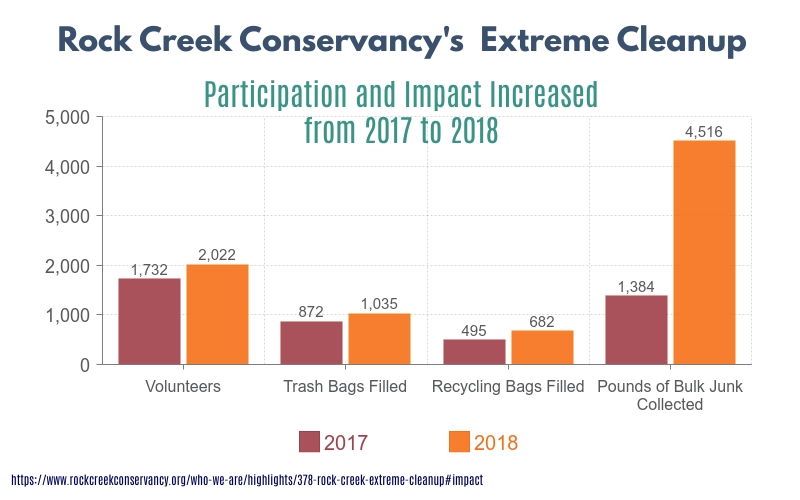

More than 4,500 pounds of such waste was collected in one day last year during Rock Creek Conservancy’s annual Extreme Cleanup, the largest trash removal event for the park. 2018 was the event’s 10thanniversary and saw an increase in participation and impact from the prior year.

The Extreme Cleanup is part of the Alice Ferguson Foundation’s annual Potomac River Watershed Cleanup, which occurs at almost 300 sites across four states—Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania—and Washington, D.C., in April. Over 346,000 pounds of trash were collected by more than 9,700 volunteers in last year’s 30thanniversary cleanup. Since the event’s inception in 1989, more than 150,000 volunteers have removed over 7.5 million pounds of trash.

Part Four – What a Dump!

The bucket and all the other trash gathered today is collected by the National Park Service. The majority of the city’s trash is processed by the Fort Totten Transfer Station, and District residents are welcomed to bring their solid, hazardous, and electronic items there for disposal every Saturday. The city’s dump is a popular place. “What a dump!” many of its Yelp.com reviews read.

The site averages between 200 to 600 cars of people with junk on the days that it’s open to residents, according to Chris VanNamee, an employee of MXI Environmental, who is contracted to manage the household hazardous waste collection at the Fort Totten Transfer Station. VanNamee handles items such as fertilizers, pesticides, antifreeze, car oil, and cans of paint. The paint is sorted and shipped to a facility in Virginia where it can be recycled.

The overall percentage of the District’s trash that is diverted from landfills or incineration through recycling is below both national and regional averages. The city’s waste diversion rate is only 23%, according to “Trashed,” a recent three-part series by WTOP. This is quite modest compared to its surrounding counties. Montgomery County, Maryland’s rate is 62%. Prince George’s County, Maryland’s rate is almost 65%. Arlington, Virginia’s rate is 49%.

The five-gallon plastic bucket could be processed by VanNamee’s group, which would need to determine what it contains. “We can test it to find out whether it’s a base or acid or see if it has oxidized,” he says. “We can figure out what the material is, so we know what waste stream to put it in.”

Until then, the bucket remains with the pile of trash bags that the stream team has collected. Meanwhile Furberg and Tallent head back to their scuba store, which is closed on Sundays to catch up on work.

Their store is having a fall clearance sale next week to unload discontinued and overstocked scuba gear. Wet suits, fins, masks, boots, dive computers, regulators, and buoyancy compensation devices—all various manifestations of plastic—must get marked down. Yes, even Furberg has a plastics problem.

Yes, even Furberg has a plastics problem.

As a diver, Furberg depends on plastic for the life support that enables him to pursue his passion for the ocean and the business that provides his own livelihood. In other words, plastic helps him explore the damage that plastic causes his beloved oceans. It is a dilemma that many in a plastic-dependent society can relate to.